On a recent Arvid Kahl podcast, Channing Allen described Indiehackers.com as a "community-powered media company." It's been weeks since I listened to the episode, but that idea of a community-powered media company has stuck with me because it clearly describes a shift I've also observed. Community-powered media companies represent a fragmentation of social networks into smaller, focused communities where any member can contribute.

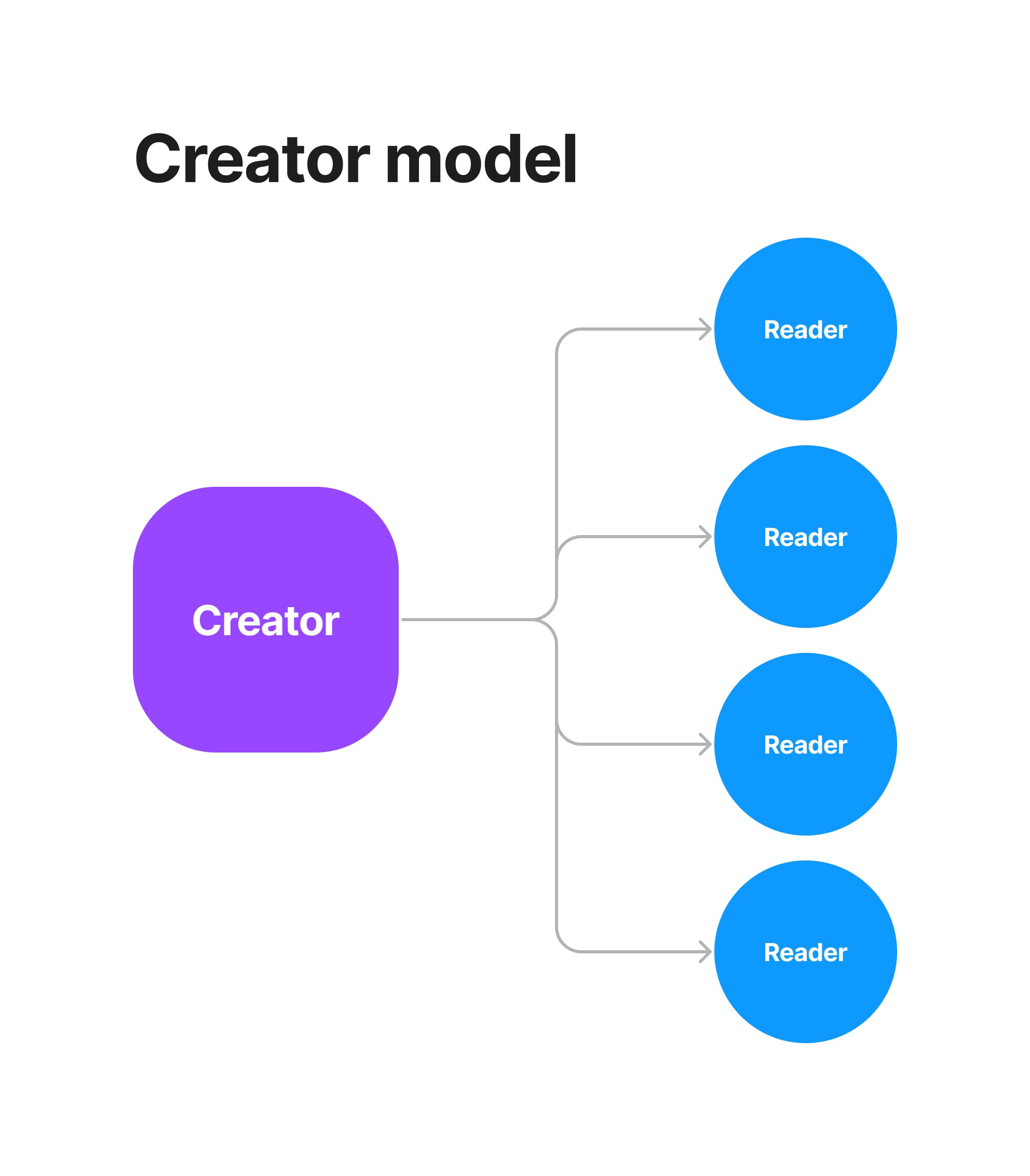

The Creator Model

The classic creator model involves one person creating content and a community of readers who consume it. A great example of this model is Substack, where authors broadcast posts to their audience. The passive follower model has long been successful but requires ongoing content creation to maintain audience engagement. These businesses tend to lack network effects because the creator's content doesn't improve as the number of readers increases.

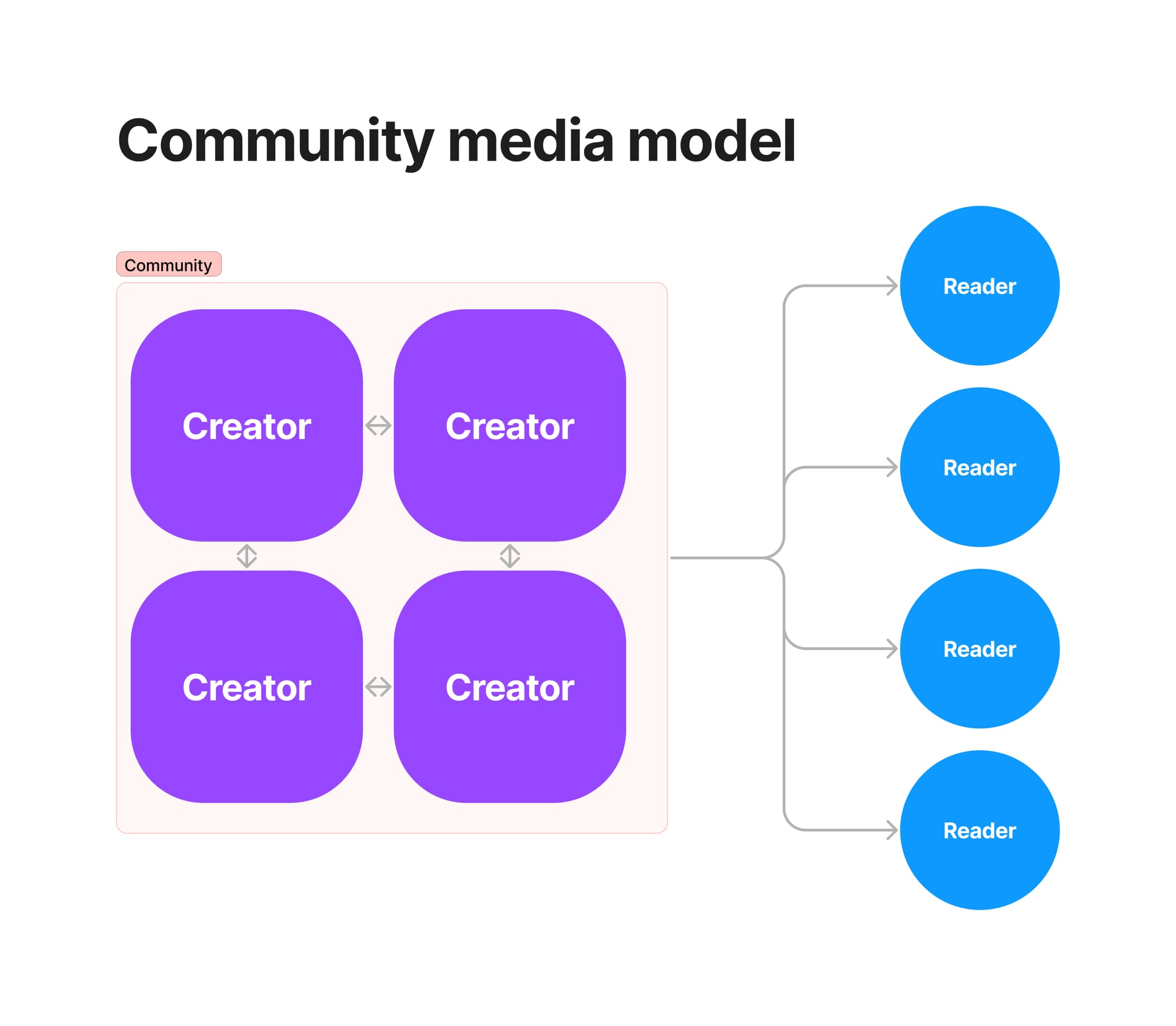

The Community Model

Indiehackers started as a creator-led model, but they allowed others to post over time. Now, the site is predominantly community-created content. Community members share on Indiehackers because they can engage like-minded people without building a personal audience. Nobody likes shouting into the void. For Indiehackers, this approach creates more content from more perspectives and shifts the burden of content creation from the site owners to the community. Plus, discussions create nested engagement opportunities on posts, so interested readers can converse instead of just reading.

At the core of the community model, a group of community members talks to each other, and the rest of the community follows those discussions. However, these communities can harness network effects because as the community grows, it has more content, making it more compelling to join. More content creates a data opportunity to find and broadcast only the best information to each member, which can further increase engagement and retention.

1% Rule and Minimum Viable Community

The key to community-led media is making it easy to follow the content. While making Moonlight, I spent a lot of time coding buttons and app interfaces. But one day, I looked at the data and realized that our newsletter had ten times as many weekly active users as our entire website. It turned out that the newsletter was the product for most people, and only a highly engaged minority logged into the website.

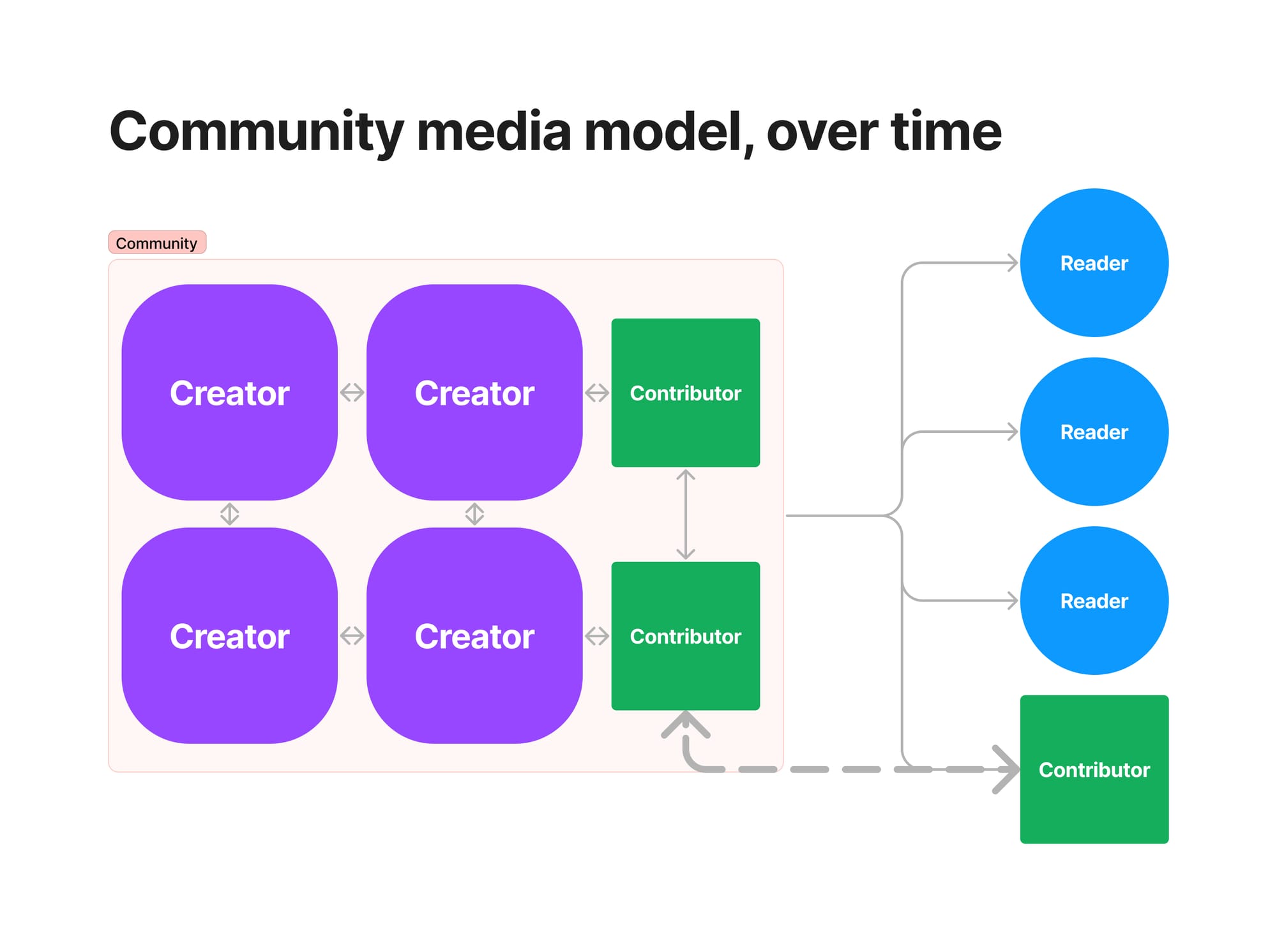

This engagement distribution is typical – the 1% rule states that, in most internet communities, 1% of users create content, 9% engage with content, and 90% consume content silently. Lack of engagement is a problem many people encounter with community building – but the core issue is that most people prefer to consume passively.

To bootstrap a new community, the creator needs to embrace being an active creator of content, and as a rule of thumb, you need a thousand members to have about ten active creators. So, the community media company starts as a creator-led model; then, over time, it can shift to a community-led model.

This distribution between creators and readers explains why chat-based communities tend to decrease in engagement over time. Chat makes posting easy, but following a chat-based community engenders constant context shifts. Opening and reading hundreds of messages in dozens of channels is tedious, not enjoyable. And, as a community grows, most people want to glean only the highlights of discussions.

Infrequent Contributors

One of my favorite parts of community media is the infrequent contributors. With creator-led media, the creator has to make content, even if they don't have anything to share. In community media, the contributors can change day-to-day. The FRCTNL community is a good example, where a member may have a job post to share every 3-6 months. That's not enough to build their own Substack around. But, by joining a community, they can stay engaged as a reader and then, every few months, become a contributor by posting a job in the group. Even though their posting may be infrequent, it adds value to the community. And, across all readers, the occasional contributors add up to valuable content, which tends to be organic and high-quality.

Hybrid Approaches

Many creator-led businesses have explored adding a community to keep readers engaged, especially the most active members who want to contribute. For instance, Lenny's Newsletter runs a Slack community for subscribers. For years, he's used the community to craft an additional "Community Wisdom" email every Friday, separate from his core essays.

This approach of adding a community to existing creator-led businesses will become more common. The hybrid content strategy keeps more readers engaged and active while recognizing community members for their contributions. And, it can reduce stress on the creator by providing feedback and ideas on their work.

Lenny’s Newsletter does community media correctly by summarizing activity in an email instead of relying on chat as the primary consumption method. By curating a short weekly email, all readers can follow the community without reading every message. But, it’s a lot of work to curate this community summary – manually monitoring chat, curating content, and writing posts. Lenny seems to have a separate person focus on the community media emails, but that’s not an accessible solution for most creators.

For most readers, "community" is a read-only channel, not an app they want to log into. This dissonance explains why apps such as Discord and Circle have struggled to gain traction in the creator-led space - they focus so much on getting members into their apps that they alienate the people who want just casually to follow.

Booklet

I've recently launched Booklet as a community software platform. I began building it as an asynchronous alternative to Slack by focusing on threaded discussions instead of chat and a daily email summary instead of constant push notifications.

As I've run Booklet communities and helped others run theirs, I've realized that the "Community-powered media" model works well with Booklet. Some people talk, but everybody can follow discussions through the email summary. The threaded posts keep discussions organized for easy browsing, and Booklet's use of OpenAI means that summary emails stay brief and high-quality, even as the number of posts scales.

Many community managers may hesitate to consider themselves “media companies.” But, as I’ve talked to Booklet users, I’ve realized that many people find a sense of belonging by following the conversations in a community. They feel an identity alignment with the group and don’t want to engage frequently. However, the periodic email summary helps them decide when to jump in and contribute.

Conclusion

As Facebook slowly dies and as Twitter X continues to be a dumpster fire, people are seeking more niche communities where they can participate. While synchronous chat communities worked during the pandemic, as people emerged from lockdowns, they lost interest in sitting in front of a chat app all day. Creators have already figured out that asynchronous content engages their audiences, and more will realize that they can turn their audience into a community.

If you have an audience or community and are looking for a way to engage them, send me an email. I’m working on some Booklet features to automate some steps for adding a community to an existing business, such as automatically syncing subscribers from Substack and Stripe. I hope these Booklet features help more people build communities that keep people engaged without making them feel overwhelmed.